Shove Memorial Chapel

Tour Stop: #12

Current and Historic Name: Shove Memorial Chapel

Address: 1010 N. Nevada Ave.

Year Built: 1931

Architectural Style: Norman Romanesque

Architect: John Gray, Pueblo

Designation: National Register

Access Level: Shove Chapel is a non-denominational place of worship. The public is invited inside.

In the depths of the Great Depression Colorado College built a long-awaited chapel that is considered one of the finest examples of Norman Romanesque architecture in the state. F. Edward Little, a member of the Class of 1935, recalled the importance of Shove Memorial Chapel to the college community during those hard economic times:

An 1874 master plan for Colorado College proposed a chapel in the center of the campus, with paths radiating outward, reflecting the importance of religion in its early history. The institution's stated purpose was "to build a college in which liberal studies may be pursued under Christian influences." The college was founded with the support of the Congregational Church, its early presidents were ordained ministers of the church, and most members of the board of trustees came from that denomination. Auditoriums in Cutler Hall and later Perkins Fine Arts Hall hosted daily worship sessions, and students attended services at the First Congregational Church on Sundays. In 1907, the college amended its charter to provide that the institution would be nonsectarian, although it required student attendance at daily religious services. Responding to the preferences of students in 1927, the college made such attendance optional.

Although the college gradually granted students greater freedom in their spiritual lives, President Charles C. Mierow (1923-34) and others believed that a separate chapel was an important and needed facility for the campus. Trustee Eugene Percy Shove's decision in 1928 to provide funding for the construction and endowment of a chapel to honor his clergymen ancestors was an unprecedented gift. The construction costs amounted to $316,000, later supplemented by a $100,000 endowment for maintenance and programming. Shove played an active role in the plans for the chapel, demanding the finest materials and artisanship despite the economic downturn during its construction.

Shove, a prominent Colorado Springs businessman, played significant roles in mining, banking, and the sugar industry in Colorado for half a century. Born into a Quaker family in New York in 1855, he attended Ithaca Academy, Cazenovia Seminary, and Syracuse University. In the early 1880s, he moved to Gunnison, Colorado, where he was first engaged in mining and then served as an organizer and cashier of the First National Bank. In 1896, Shove relocated to Colorado Springs, which was in the midst of a tremendous economic boom resulting from gold mining discoveries at Cripple Creek. He became a partner in a brokerage business in the city, invested in gold and copper mines, and continued in banking. He served as vice president of the mining stock exchange, president of the El Paso National Bank of Colorado Springs, chairman of the board of directors of the First National Bank of Colorado Springs, vice president and organizer of Golden Cycle Mining and Reduction Co., and treasurer and founder of both the Cresson Gold Mining and Milling Co. and the Holly Sugar Corporation. Like a number of men who became millionaires as a result of the Cripple Creek gold boom, Shove developed an interest in the affairs of Colorado College, serving as its vice president, a member of the board of trustees during 1914-39, and a two-time chairman of the board.

This

Building

in

History:

In 1929 Gray established a private practice in Pueblo. Shortly afterwards he submitted his designs for a chapel at Colorado College, and was selected from a group of nine architects in a national competition. Apart from small residences, Shove Memorial Chapel was Gray's first commission completed in his own name.

With gold beanies, green hair ribbons, and black sweaters our campus social life began in 1946. Once accepted into the school community, it was sloppy Joe sweaters, saddle shoes, and bobby sox.

The chapel is of pure Romanesque architecture and leans toward the severe Norman interpretation of this style rather than the more florid Southern type of Southern France and Italy.

The large stone building is in excellent condition and is almost unchanged from the time of its construction. The building is significant for its representation of the Romanesque style and of the work of architect John Gray, as well as for its high artistic values reflecting the work of Robert Garrison, Robert Wade, Joseph Reynolds, Jr., and others. The building encompasses important interior features that contribute to its significance.

The college staged a national architectural competition to select a designer for the chapel. Fourteen architects were invited to compete, including some of the foremost firms in Colorado, as well as companies in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. President Mierow, members of the board of trustees, Eugene P. Shove, and Denver architect Lester E. Varian served as jurors. The jury selected Pueblo architect John Gray to receive the commission for the chapel project. Gray devoted himself to the task, and Shove Memorial Chapel, the first major building he designed after establishing his own practice, is considered his finest work. Gray, born and educated in Scotland, had trained and worked in Chicago before moving to Colorado for his health. In Pueblo he became associated with the firm of William W. Stickney, which designed the National Register-listed Colorado Springs Day Nursery. Gray also worked in Denver with Merrill H. and Burnham Hoyt, designing the 1928 St. Martin's Chapel of St. John's Cathedral. Gray's plan for Shove Memorial Chapel was all-encompassing, ranging from the character of the door hinges to the creation of the print on the memorial tablets. As President Mierow judged, the building reflects ". . . the skill and loving care of the architect who was not content with his vision of this beautiful college cathedral until he had realized its actualization in every detail."

Designed in the Norman Romanesque style, the mass and proportions of Shove Memorial Chapel were inspired by Winchester Cathedral before its remodeling in the 15th century. The model was considered appropriate, as one of Eugene Shove's ancestors had been ordained in the cathedral in 1600 and John Gray had married there. The architect indicated he approached the design of Shove endeavoring "to recreate that elusive sense of mystery and the devotional atmosphere of the ancient cathedrals and to subordinate all other considerations for this purpose."

An elaborate cornerstone laying ceremony for the chapel in October 1930 included an academic procession to the building site and participation of the Grand Master of the Masons of Colorado. Eugene P. Shove and Rev. Irving B. Johnson, the Episcopal Bishop of Colorado, placed ancient stones from several religious buildings in England in the chapel walls. Construction of the chapel provided work for a number of craftsmen at a time when the country was experiencing widespread unemployment. Platt-Rogers, the contractor, hired only Colorado Springs workers to construct the chapel.

The architect initially specified Colorado red sandstone, similar to several other campus buildings, for the chapel walls. This plan was abandoned due to a lack of modern stonecutting plants in the state and the greater cost of the stone. Instead, Bedford, Indiana, limestone was selected and imported. The building required 1,000,000 bricks manufactured in Colorado and 650 tons of limestone. Workers in Indiana cut each piece of stone to precisely fit a certain location on the building. When a carload of stones went missing, it resulted in construction delays since the pieces were not interchangeable.

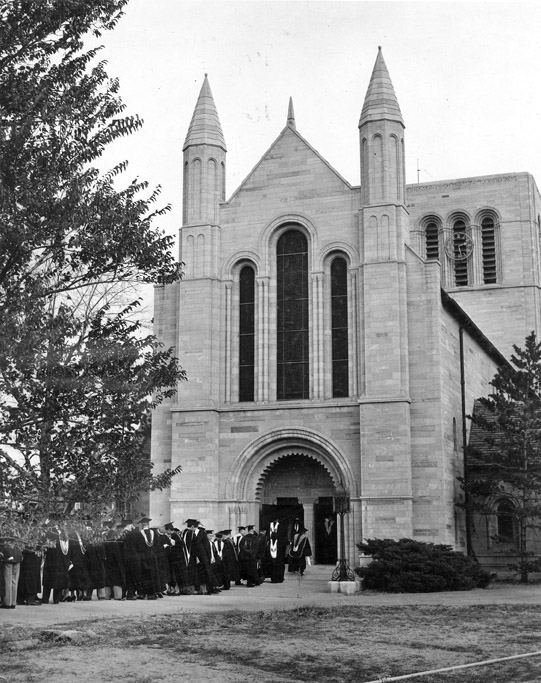

Faculty and students in academic regalia marched to the completed chapel for its morning and evening dedication ceremonies on 24 November 1931. Shove was the first new building built on the campus since 1914 and the last to be erected in stone. President Mierow presided at the dedication, and principal speaker Rev. Bernard I. Bell, president of St. Stephen's College, observed that the chapel "stands here, adjacent to the halls of learning, not merely for the promotion of human fellowship but for something vastly greater. It stands for the necessity and the possibility for a search of learned people for spiritual values."

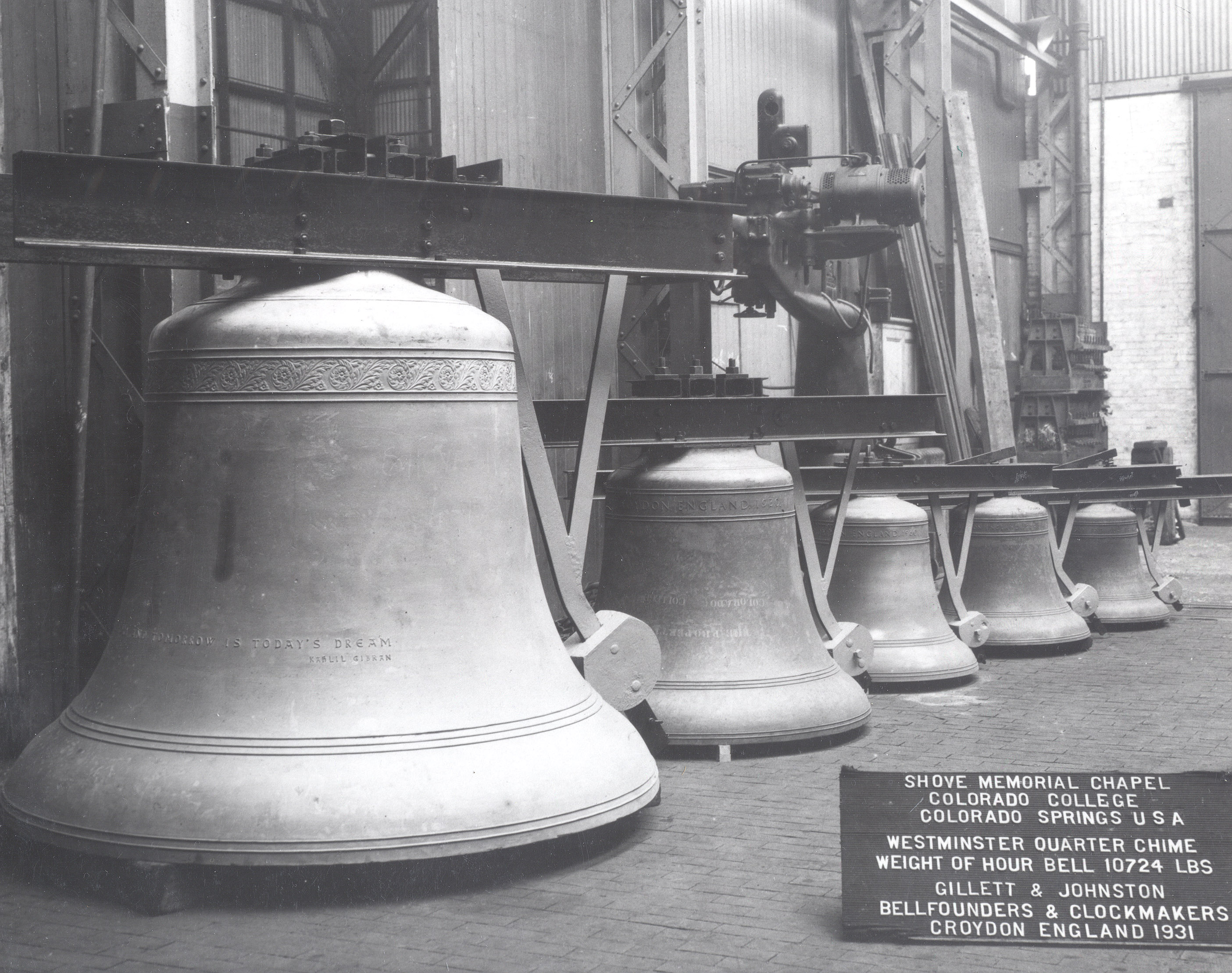

Believing that using recorded chimes in the chapel tower would be "unworthy" of the building, John Gray commissioned the Gillett and Johnston, Ltd., foundry of Croydon, England to produce a set of bells. The firm, which also fabricated the skeleton clock on the west wall of the tower, was one of the largest and most respected producers of carillons in the world. Gillett and Johnston also produced bells for the Cleveland Tower of Princeton University and the Chicago University chapel. The Shove tower has five bells tuned for Cambridge (Westminster) quarters. The bells were described as "probably the finest sounding chimes in the entire west, the clear notes of these bells ringing the hour and quarter hours is a welcome touch to the community life of the college environ." During the night, the front of the chapel and the tower were floodlighted when the bells sounded between 5 p.m. and 10 p.m., illuminating the clock face. It was believed the chapel was the first building in the country with such use of controlled floodlights. An inscription from the work of Kahlil Gibran was etched onto the hour bell: "Yesterday is but today's memory and tomorrow is today's dream." After being cast in England, the hour bell was shipped by steamer to New York, then passed through the Panama Canal and was unloaded at San Francisco, where it traveled by rail to Colorado Springs. Shove boasted the largest and heaviest (10,759 pounds) hour bell in Colorado until the University of Denver acquired a bigger one in 1999.

The chapel received a 40,000-pound Welte-Tripp Organ Company concert type pipe organ in 1931. A representative of the firm stated that the instrument was the "finest organ ever built by our organization." It was crafted "with emphasis on features of tonal and physical beauty to coordinate with the new Colorado College building." Grace Church and St. Stephen's Church in Colorado Springs also installed a Welte-Tripp organ. Organ historian Rich Morel observed the Shove organ was built before the advent of television, at the end of a golden age when churches, theaters, auditoriums, and many wealthy residences had such instruments.

Artists and craftsmen from around the country worked on aspects of Shove to complete the carefully planned, meticulously detailed design by John Gray. Sculptor Robert Garrison created the exterior stone carvings, including two gargoyles, the tympanum over the main entrance, and carved heads ornamenting the west entrance and the east window of the Morning/Pilgrim Chapel. Born in Iowa in 1895, Garrison studied at the Pennsylvania Academy and with John Gutzon Borglum, who is known for his work on Mount Rushmore. In 1919 Garrison moved to Denver, becoming the director of the Denver Academy of Applied Art the following year. His commissions in the city included the designs for bronze mountain lions at the Colorado State Office Building, fountain figures at the Voorhies Memorial reflecting pool, and architectural features for the Ideal Building, the Midland Savings Building, and South High School. He moved to New York in 1930.

Master stone carver John Bruce, who had worked on buildings in San Francisco and Denver, carved the ornaments for the building using models provided by Garrison. The stonework of the walls required exacting skill, as each piece of limestone was cut for a specific site on the structure. Garrison sent the models for the carvings from New York, and Bruce prepared the actual works at the construction site. Two gargoyles, one on the south face of the Morning/Pilgrim Chapel and the other on the east face of the tower, are both ornamental and also remove excess water from the roof. The figures were based on a timber wolf and a mountain lion because Garrison believed that local animals would be more proper and interesting. Curiously, "J. Bruce" and an 1880 date are carved in the upper stonework of Cutler Hall.

Robert E. Wade, described as an "authority on design and painting of church interiors," planned and painted several of the ceilings in the chapel, including that of the vestibule, the crossing, the chancel, and the Morning/Pilgrim Chapel. Born in 1882, Wade studied art in Boston and Europe and worked as a mural designer and colorist with the Boston architectural firms of Cram & Ferguson and Allen Hall & Co. Wade also painted features in the Robinson Chapel of the Boston School of Theology, and the Chapel of Emmanuel Church in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and in the National Register-listed Lincoln School in La Junta, Colorado.

Joseph Reynolds, Jr., of the nationally recognized Boston firm of Reynolds, Francis, and Rohnstock, designed and fabricated the stained glass windows. The firm had previously created windows for Wellesley College. Eugene Shove agreed to pay for all of the windows himself, with the expectation that he would be repaid as memorials were purchased. The windows of each section of the chapel relate to a particular theme, with the iconography determined by Reynolds, the college president, and the architect. The artist stated that he designed the stained glass in a "primitive and archaic manner."

From the time of its completion, the building encompassed a variety of activities in addition to weekly religious services. College rites of passage such as commencement and insignia day took place in Shove. Public meetings, speeches, and receptions occurred in the building. The Department of Religion utilized its basement lecture hall.

The chapel continues to offer the campus community a place for classes, lectures, meetings, and a variety of programs, including two concerts of the college choir each year. The chapel is a popular venue for weddings due to its traditional architecture and its interfaith nature. A significant musical program, including an on-going Distinguished Organists Series, has brought the world's finest organists to Colorado College. The architectural and historical significance of Shove Memorial Chapel received recognition through its listing in the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.