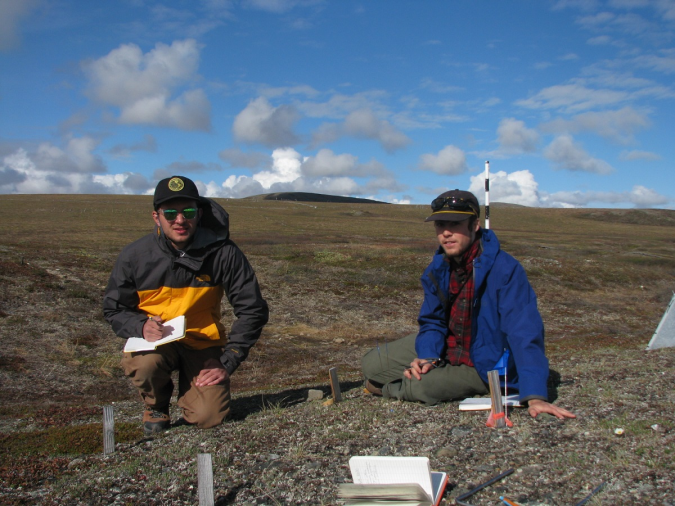

Two Colorado College students will spend most of this summer in the Alaskan Arctic conducting plant ecological research.

John Feigelson '19 and Hayes Henderson '20 are working with Roxaneh Khorsand, a visiting professor in Colorado College's Department of Organismal Biology and Ecology, who recently received a $22,223 Research Opportunity Award from the National Science Foundation for her project, "The effect of climate warming on plant-pollinator interactions in the Alaskan Arctic." The grant is in conjunction with Steve Oberbauer, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida International University, and represents a collaboration between a liberal arts college and a research institution.

Additional funding from Colorado College allows Feigelson and Henderson to spend eight weeks working at the Toolik Field Station, the U.S.'s most important arctic research station and the site of the National Science Foundation's Arctic Long-term Ecological Research Site, located just north of the Brooks Range.

"The effects of climate change are particularly visible in the Arctic because rapidly retreating sea ice creates a positive feedback that further exacerbates warming," says Khorsand, who is making her second research trip to the Alaskan Arctic. "Increases in temperature have cascading effects across all ecosystems. As a plant ecologist, I focus on the terrestrial systems. Changes are happening right before our eyes so we can measure these changes and predict future changes."

Feigelson, Henderson, and Khorsand, who conducted her post-doctoral research on plant reproductive responses to climate change, departed for Alaska shortly after Colorado College's Commencement.

"The Toolik Field Station has always been on my radar because of the field research that has come out of there," says Henderson, an environmental studies major from Bethesda, Maryland. "I've read papers that have had their field research based there, so I'm excited to now contribute to that research."

"It's exciting to have a faculty member put their faith in you," says Feigelson, an organismal biology and ecology major from New York City who will serve as the department's paraprofessional next year. "It's a great opportunity to conduct research that has a direct application so soon after graduation."

Feigelson and Henderson will test the effects of climate warming on plant phenology (the study of cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena) and reproductive output, using control plots and experimental plots with open-top chambers. Open-top chambers are widely used to study the effects of elevated CO2 and other greenhouse gases on vegetation. They are similar to open-top, mini greenhouses; plastic enclosures set on top of the land that interacts with the outside environment by capturing heat, but allowing precipitation and insects to enter.

Khorsand's research will examine the effect of heat on plant reproduction, looking at when plants flower, how much they flower, and how effectively flowering translates to fruit and seed production. It will also look at the presence - or absence -of pollinators. It's been documented that many plant species in the Arctic are responding to climate change by flowering earlier. What Khorsand, Feigelson, and Henderson are looking at is how this will affect species interactions; will pollinators also be available earlier to do their part in the seasonal process? Not only will the team quantify potential mismatch between plant species and pollinators, the researchers will also compare the effects of warming on insect-pollinated versus wind-pollinated plants. "Understanding how different pollination systems respond to climate change will allow us to predict how plant species diversity may change over time," says Khorsand

"We're interested in seeing if insect species also are shifting," says Khorsand. If plants and pollinators don't shift together, it results in a mismatch. "Mismatches between plants and pollinators can have potentially profound implications for plant reproductive success, yet relatively little is known about this topic," she says. "The low diversity of plant-pollinator communities in the Arctic relative to temperate systems, coupled with the short growing season, highlights the particular vulnerability of arctic plant-pollinator interactions." Khorsand adds, "A critical concept in ecology is species-specific responses. That is, not all species respond to environmental change in a uniform manner. Some plant species are doing better because of climate change while others are not. We want to learn about plant reproductive patterns in the Arctic so we can inform management and the general public. My goal as a scientist is to use science to effectively conserve biodiversity."

In addition to the NSF funding, internal funding came from Colorado College's Department of Organismal Biology and Ecology, Natural Science Executive Committee, and the Dean's Office.