President Joe Biden recently announced the creation of the country’s newest national monument, protecting tens of thousands of acres in the mountains of Colorado from mining and development. The designation preserves a site of great historical interest, an area that was home to the Ute people long before recorded history and remains culturally important. The Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument protects more than 53,000 acres of rugged and visually rich terrain with broad recreation opportunities.

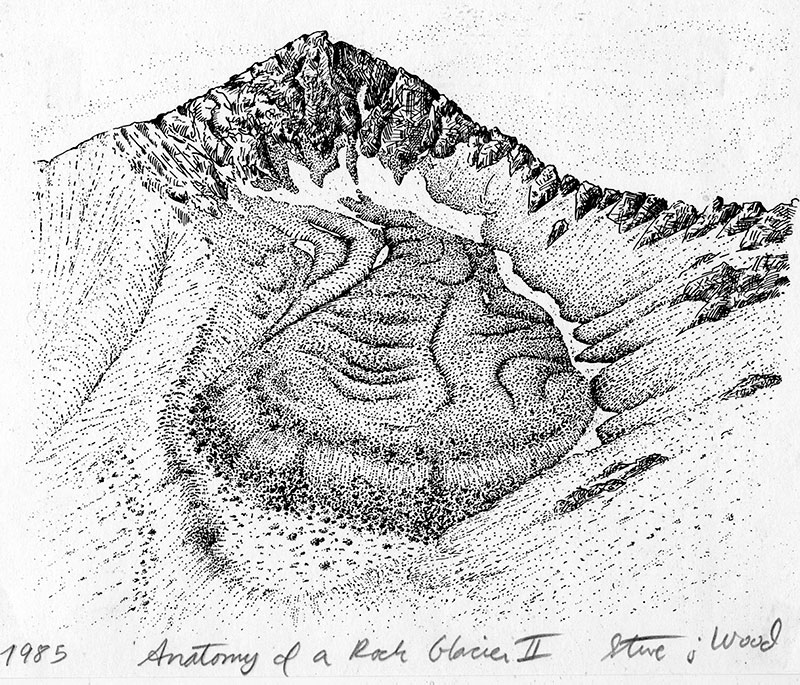

The official monument proclamation refers to the Spruce Creek rock glacier: “Studied for decades, the Spruce Creek rock glacier, which is fed by a rockfall from Pacific Peak’s northeast cirque, has advanced our understanding of the flow mechanics and morphology of rock glaciers.”

Eric Leonard, professor emeritus of geology, recognized this reference. He’s been studying the Spruce Creek rock glacier, along with CC students and other CC staff, for a long time. “As far as I am aware, ours is the only in-depth study of a rock glacier in the monument,” he says of the research project that began back in 1985.

A rock glacier is a mass of rock fragments and ice that flows slowly downslope under the influence of gravity. They are common throughout the Colorado mountains and in other ranges in the west.

Leonard, prompted by interested students, developed a course to study rock glaciers in Fall 1985. That initial class established a survey network at Spruce Creek rock glacier, to monitor its flow and changes in other characteristics. Over the succeeding years, Leonard returned numerous times, with new groups of students, to redo the surveys, most recently in Fall 2019.

“We set up a survey network of marked boulders that could be used, through time, to assess the flow, deformation, and thickness changes of the rock glacier,” says Leonard of the survey’s first days. “We then did an initial survey and set of related measurements to serve as a baseline for future measurements. When we developed the project, our first goal was to use the repeat measurements to gain a better understanding of the mechanics of rock glacier flow and of the internal composition of the rock glacier – neither of which was well understood at that time. Additionally, we thought that we might be able to observe changes related to future warming and possibly to document past responses to earlier climate changes.”

In addition to the resurveys, students have undertaken projects trying to reconstruct the history of the Spruce Creek rock glacier using a variety of other methods — ranging from detailed measurements using old aerial photographs, to using biological and isotopic methods to reconstruct a multi-thousand-year history of the rock glacier and how it has responded to past changes of climate. Over the years, 19 CC students have contributed to the research.

The work has led to a fuller understanding of the rock glacier – its composition and its movement. It has also shown that the rock glacier has indeed responded to climate changes over many timescales – including by thinning and slowing over the last several decades.

Leonard says he is thrilled to see this area preserved as part of a national monument. “It is a magnificent region of high-mountain terrain with great potential for scientific research.” CC’s work at the Spruce Creek rock glacier is continuing as new generations of students make use of new technologies to provide insights into the geologic and climatic processes operating there.