By Anna Squires ’17

Photos by Lonnie Timmons III

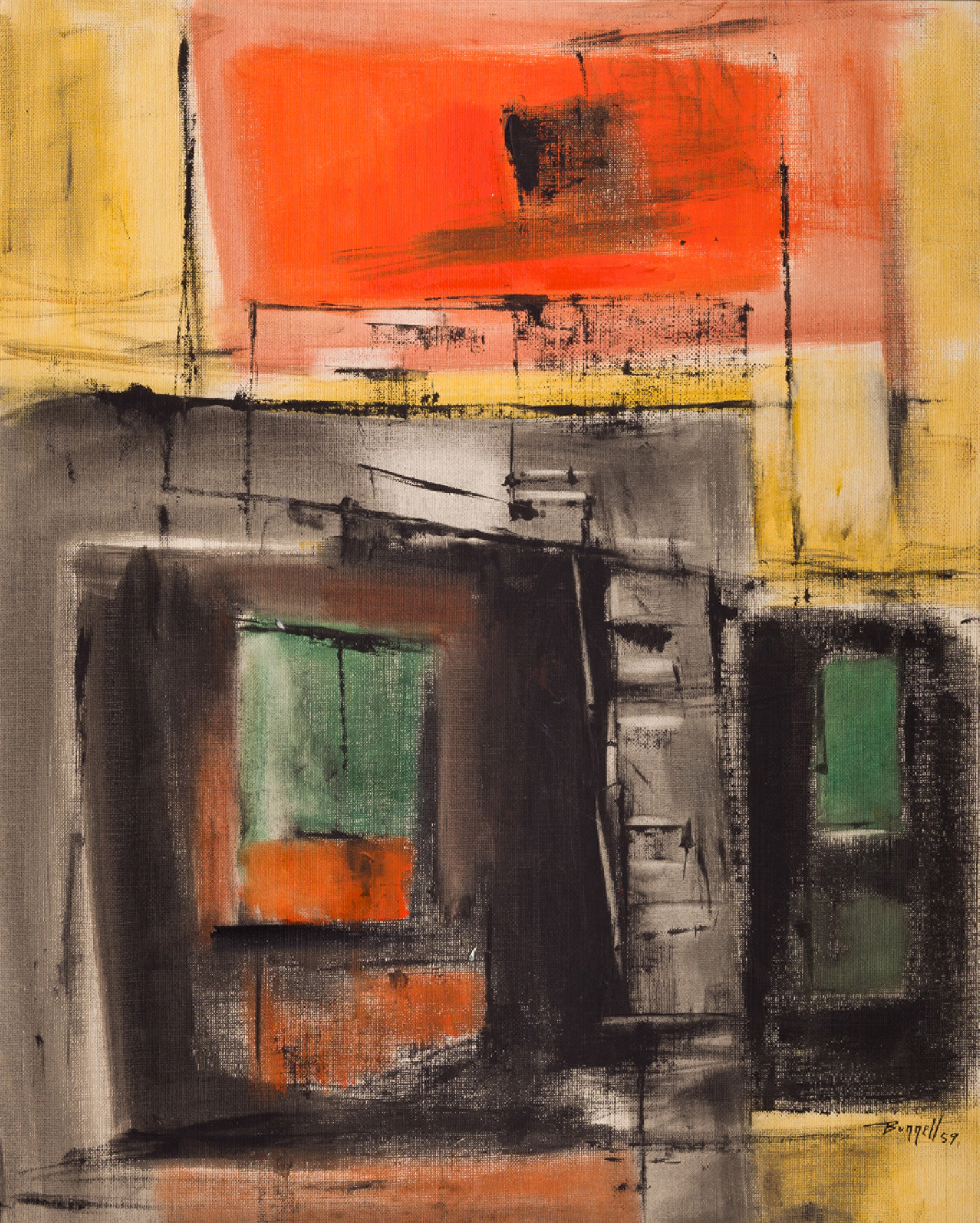

In a darkened studio, lit by scattered golden lamps, a dancer soars through the air, twisting his body around a noose like it’s made of aerial silk. His fingers flutter like wings. He does not look joyful, but he does look free. All around him, singers cry, “Order! Order!” into bullhorns, their shouts peppered with police sirens. Swelling underneath the dancer, lifting him, is a melody, smooth and deep: “No justice, no peace.”

This is the final act of an opera called “Nehanda,” created by CC’s 2022 Pamela Battey Mitchell Visiting Artists-in-Residence: a contemporary dance company led by choreographer Nora Chipaumire and featuring dancers and singers from Zimbabwe, Togo, and Burkina Faso.

Ferocious in intensity, layered with song and movement, the five-hour production tells the legend of Nehanda, a powerful ancestral Shona spirit, who inhabited a Zimbabwean woman named Charwe Nyakasikana in 1896. Channeling Nehanda’s spirit, Charwe led fellow Zimbabweans to revolt against British colonization in 1896, before giving herself up to be hanged.

The work, Chipaumire says, is not just an opera. As a work originating in the Global South, it is a protest against our very perception of what an opera should be.

“We have all inherited this notion that opera has to be in Puccini’s style, a European style,” Chipaumire says. “Opera is political. It’s about an aesthetic. It's about power. I wanted to create this work not only as a provocation — because you can only provoke so much — but also because we can. We can tell stories. We do tell stories.”

“Nehanda,” Chipaumire explains, draws on all of the European operatic tropes we are familiar with: drama and movement layered with narrative and song, using Shona throat singing in place of vibrato. Still, it does not draw from European influence, calling instead on a powerful West African tradition of long-form storytelling through sound.

“Part of this work is to question the legacy of opera, but also to invite us all to return to the meaning of the word, which means ‘work,’” Chipaumire says. “So we dare you to say, ‘What's not operatic about it?’”

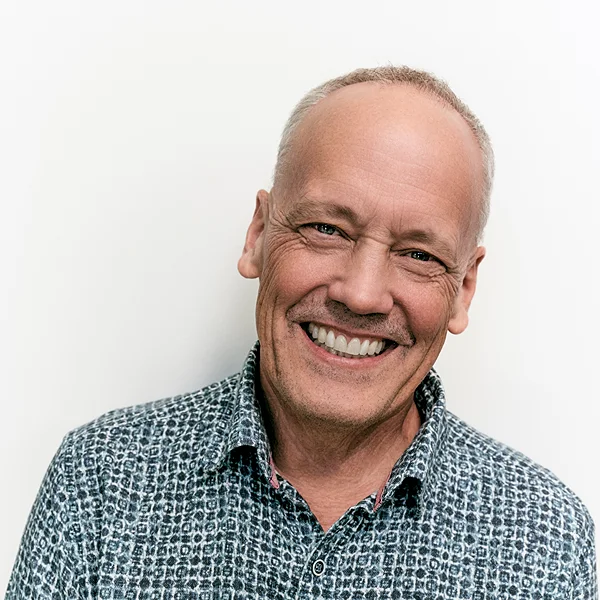

The work is also deeply political. It pulls narratives not just from Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, but also from Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I’s United Nations speech calling for an end to racial inequality. It nods, too, to the Black Lives Matter movement — and invites viewers to become participants, adding their voices and movement to the gathering. That’s why Chipaumire’s company was a perfect fit for CC’s Artist-in-Residence program, says Ryan Platt, associate professor of performance studies in the Department of Theatre and Dance.

“The Artist-in-Residence program is not about producing art as some kind of cultural artifact,” Platt says. “It’s about finding and bringing to CC people who are interested in activating the work.”

The program, launched in 2021, was created with a $530,000 gift in honor of Pamela Battey Mitchell ’58, who studied contemporary dance at CC. The “activation” Platt speaks about is part of the program’s twofold purpose: to bring artists-in-residence to CC who both teach and perform.

Chipaumire taught a Block 7 course during the 2021-22 academic year that drew from her research practice called “nhaka,” which means “heritage” in Shona. The practice is Chipaumire’s endeavor as a choreographer to create a form of movement that draws nothing from European dance tradition. Her class focused on syncopated rhythms and movements, and storytelling in the form of dance.

“It is an amazing opportunity, to have a working artist at a significant level of recognition teach a whole block to students,” Platt says. “It creates meaningful exchange with forms of knowledge that we don’t have in-house here at CC.”

Platt’s dream is that one day, the program will function as an “incubator:” an experimental laboratory for contemporary dancers to share their knowledge with CC, and to push the limits of their work.

And for Chipaumire, the work is her contribution to the lifetime-spanning challenge of racial inequity.

“There are so many deep questions yet to be resolved,” she says. “But part of being contemporary artists is to go where our elders haven't gone before.”

Chipaumire and company performed the final act of “Nehanda” on May 3 at an open studio visit, and the third and fourth chapters at a showing at the Cornerstone Arts Center on May 13. They are the second cohort of the Pamela Battey Mitchell Visiting Artists-in-Residence program.